Key Points

- In general, steer clear of "yes" and "no" to requests so that you can help reframe solutions.

- Your goal should not be to say "yes" to as many requests as possible (except by streamlining common requests).

- A solid response to a request is "yes" but with shifted requirements (to achieve higher impact).

Requests usually need to be reframed for maximum impact

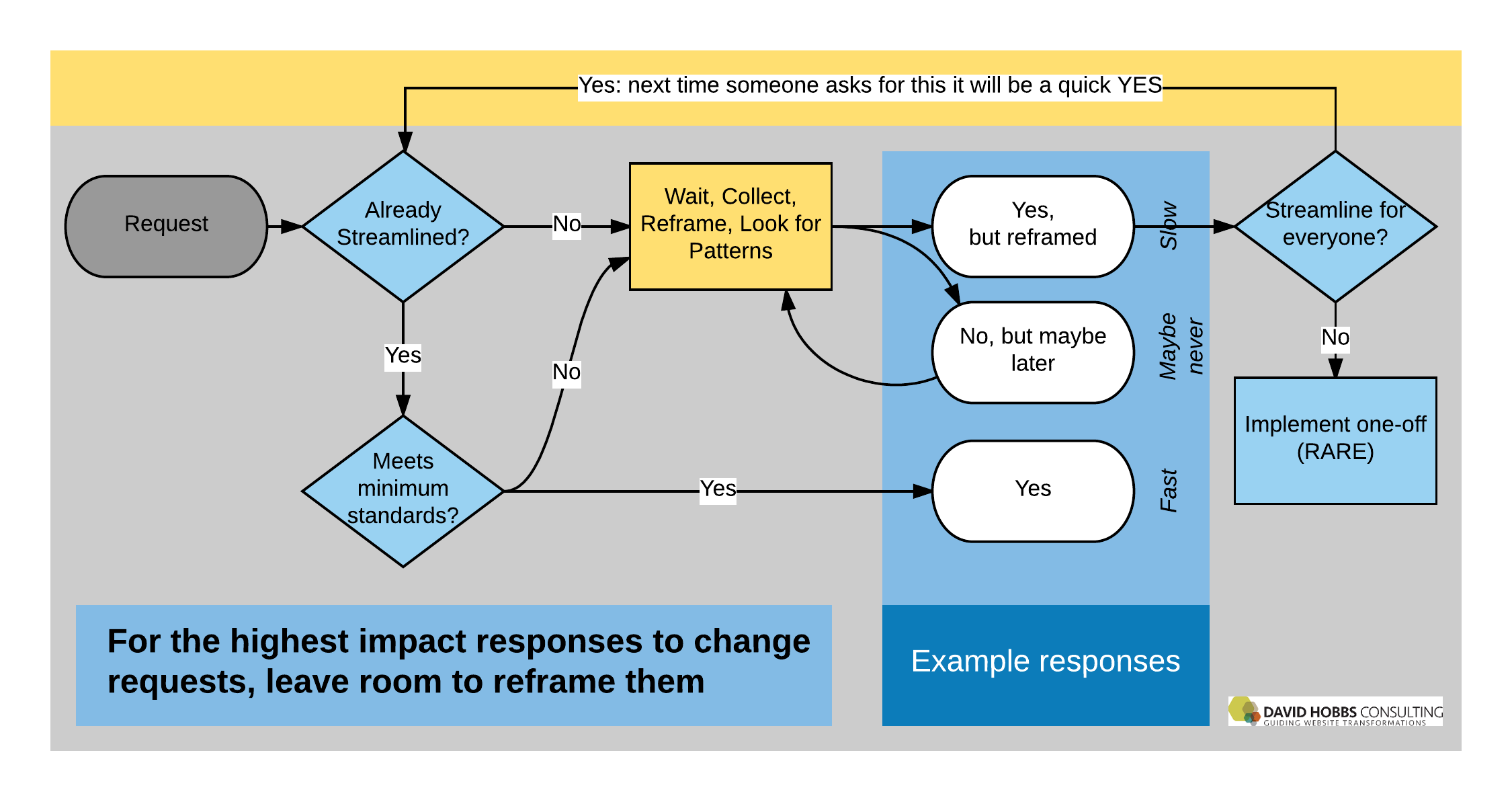

Requests for changes to our digital presence come all the time. On the face of it, it seems that saying "yes" to as many requests for changes as possible would be ideal. But this simply is not the case. For one thing, one of the quickest ways to inflexibility is by being too flexible, largely because being too flexible allows incoherent growth that becomes unsustainable. In general we need to take the time to consider requests, from seeing if other stakeholders have similar needs to digging underneath the proposed solution to what the actual need is.

Requests do not need to be reframed if you already have a streamlined process to deal with this common type of request

Of course you want common requests that serve a business goal to be streamlined. In other words, these requests should result in a rapid "Yes" assuming two things: 1) the streamlined process is already implemented and 2) the specific request is valuable and meets minimum standards. On the second point, we don't want to just be churning out junk efficiently.

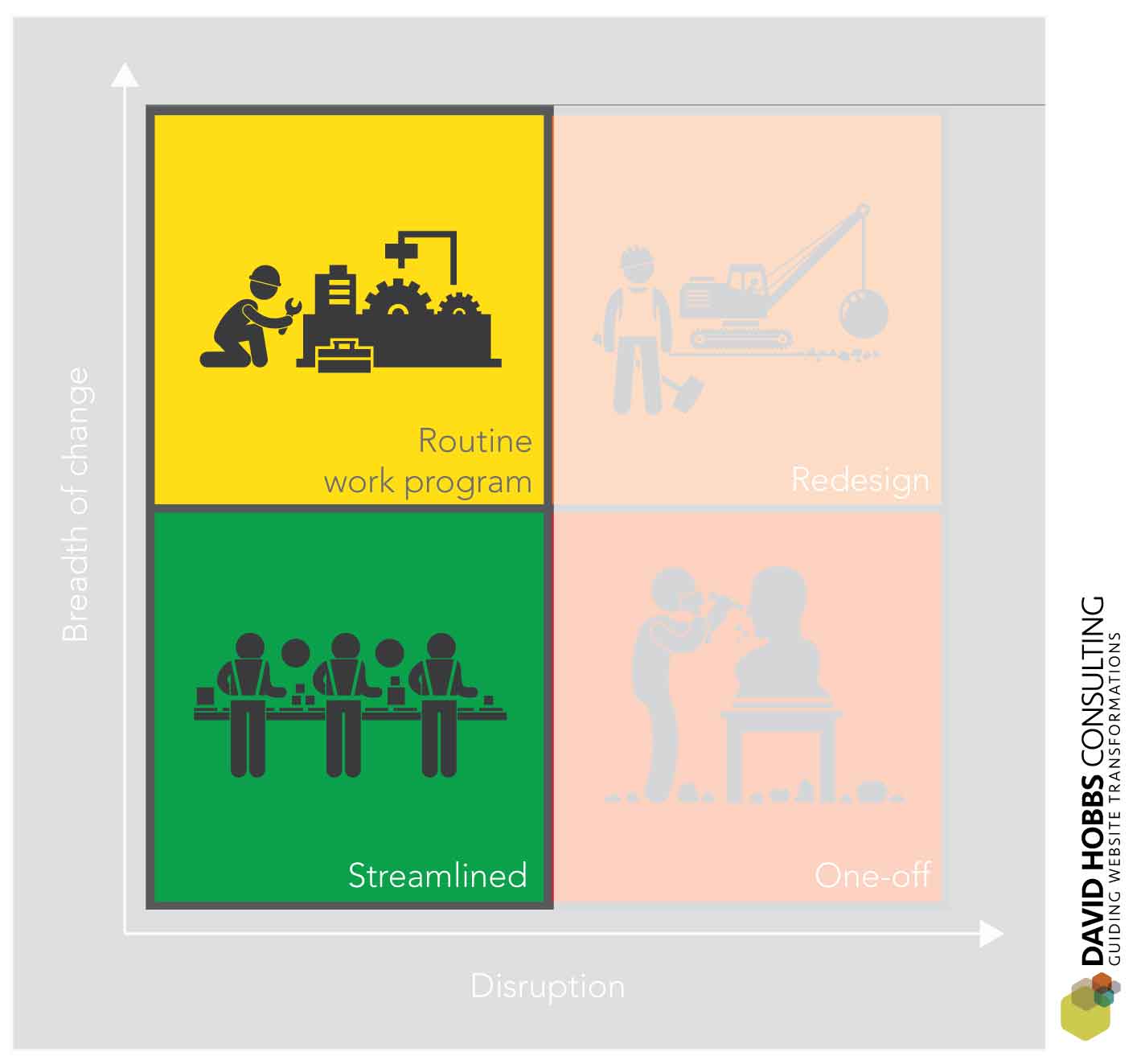

One of our primary goals in our routine work program should be to set up the mechanisms for streamlined and optimized fulfillment of standard requests. Looking at the four types of digital change, we want to push the routine work program (which is mostly concerned with improving the underlying machinery) toward improvements in the streamlined, day-to-day processes (and avoid one-offs).

Reframing requires a gap between the request and response

In order to get out of the churn of requests (and the pressure to implement what can be done quickly regardless of whether it is a good practice), we need to create a gap between the request and when any response is given. This allows the team dealing with requests to look for patterns in order to both: 1) decide what is worthy of implementation and 2) the best way to implement.

Just because something can be implemented quickly does not mean that it should be implemented quickly. In particular, your goal should be to streamline what should be fast, but only in a methodical way by first implementing it in your core systems and at that point let everyone loose to do this newly-streamlined process (rather than just letting everyone do their own thing, which means that those with more resources or abilities will get what they want but it won't be in a consistent way or help those that are less sophisticated). For instance, if you frequently have requests for a better way to display visuals, then that should be implemented in the CMS so that everyone can present visuals better (rather than simply allowing people to put in their own code to accomplish this in a one-off way, even though that would be simple to implement).

Solid responses

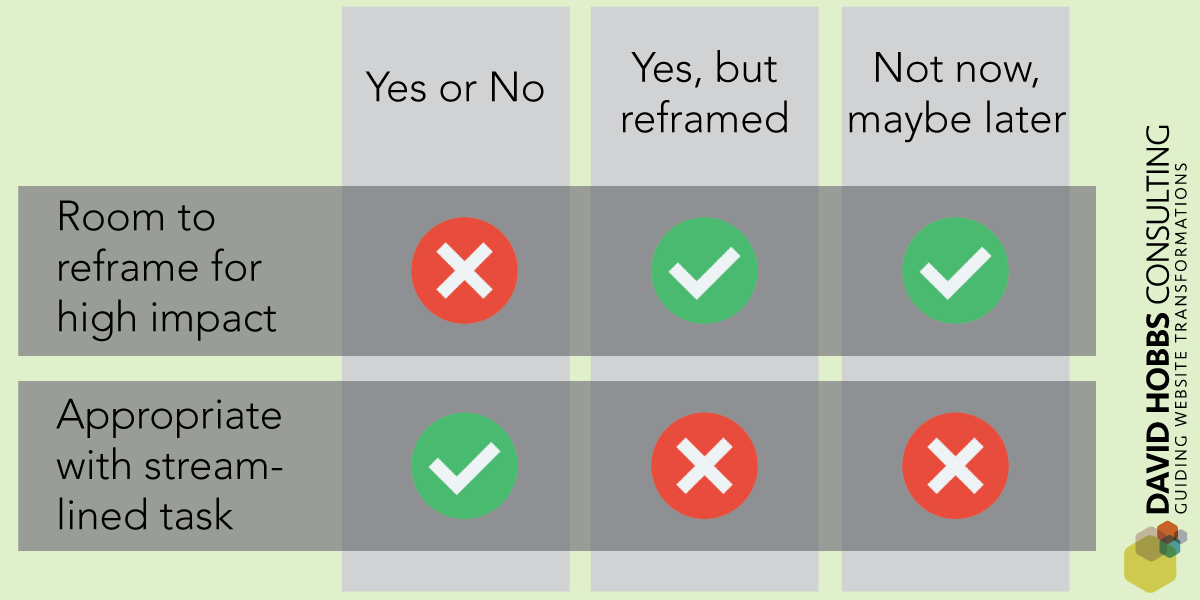

When responding to potential requests, consider using the solid responses in the first table, and generally avoid those in the second.

SOLID Responses |

When to use |

|---|---|

Yes, with shifted requirements Example: request for API to specific dataset, but instead commit to organization-wide API framework (perhaps in the next three months defining the problem) |

|

Yes, but less than requested Example: request for the ability to have any color text for a call-out box, but instead deliver a palette of colors |

|

Not now, but maybe later Example: any request that is kept in the request list but is not included in the next work program |

|

Fundamentally, we need to move from order takers to product managers — from simply executing what is requested to reframing the problem for maximum impact.

Occasional responses

To achieve that, I would recommend moving away from "Yes" and "No" and toward more nuanced responses. In particular, notice that "yes we will do that in the future" is notably NOT on the list below. In general I recommend a regular work program cycle rather than some long term roadmap, and committing to do something far in the future basically locks you in rather than being able to respond to unanticipated opportunities later. Related, note that I do not recommend saying "No" routinely either, but instead respond with "Not now, maybe later" — this allows you to watch the stream of requests to look for patterns.

OCASSIONAL Responses |

When to use |

|---|---|

No Example: request for a site that does not pass your decency standards |

|

Yes (literally as requested) Example: fix a long-standing and clearly-understood bug in the caching process |

|

Provide something not specifically requested Example: improve repository search (searching content in the backend) in order to improve the overall experience even though it is not specifically requested |

Note: although this should only be used occassionally, it can be used to great effect from time to time |

In some ways of course the "yes" response will be very common, but, especially if they are implemented as self service, they will start to become so routine that they aren't even requests that require bandwidth from the central team.

These tables originally appeared in the book Website Product Management.